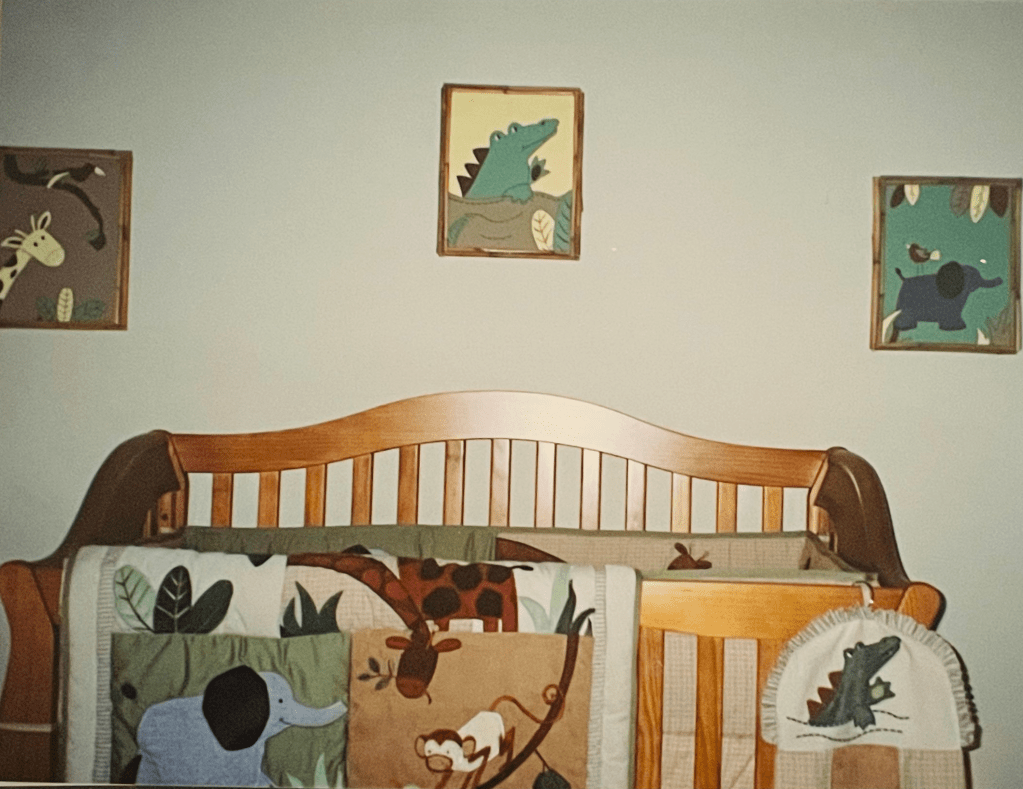

In my basement in a plastic storage container there rests a set of beloved pictures, most still framed in bamboo 18 years after I created them. Even though I used cheap glue sticks to adhere the dried grass plant to the corners and sides of the art, they peek at me intact, staring back from a time I still relive daily in parts. I spent hours at a dining room table over several months creating these nursery decorations for my first-born child’s room in the newly purchased house my husband and I found ourselves as we prepped the environment for a life with a newborn.

Because the housing market was too expensive for us to afford a home in the Lehigh Valley and my mom and dad were in a pretty community in Northeastern Pennsylvania, we decided to move near them and convinced ourselves I would somehow handle the 178-mile round-trip daily commute to the college (even while pregnant) where I worked as an English professor.

Almost 19 years later, we remain in the house and I remain at the college. I have the unfortunate expertise of knowing the best and worst places to stop along my route when one is ill from morning sickness, flu, and food poisoning, or where to empty an over-active bladder, or which parking lots are long enough when walked across to awaken a calf muscle. I have seen car and motorcycle accidents numbering in the dozens, survived snow and hailstorms and flat tires, and have been rerouted because of roadwork and Presidential motorcades. I have listened to podcasts and books, shared hundreds of hours of cell phone conversations, and chanted prayers and songs in quantities that I cannot count.

And now the son whose first bedroom walls were covered with homemade paintings of alligators, elephants, giraffes, turtles, and monkeys joins me on this long commute, because after years of working at my college, I am finally benefitting from the generous perk of a tuition waiver for my child who will earn his associate’s degree before he transfers to a four-year college to complete his bachelor’s degree. I thought the commute might break him. Somehow, we survived the first year together. His sister will join us in the Fall.

But many of my days still begin and end with me reaching out to the first-time mother I was becoming so long ago as I painted white canvas with yellows, greens, reds, and browns, all colors on F_____’s baby quilt and bumper, the two gifts my husband and I bought for ourselves when we were told the child might be okay, he might yet be born healthy and whole. Late at night after reading hundreds of pages in preparation for a world literature lecture, in a hard pine chair at one end of the table, I made deliberate paint strokes to cover the pencil my husband and I had used first to sketch the animals we wanted our son surrounded by in the nursery we were slowly organizing. And I narrated over and over in my head versions of the same story: the doctors were wrong, the ultrasounds had been misread, the heart would form correctly, the hygroma would shrink, the baby would grow larger and larger and all would be just fine.

Of course, I told myself other stories also. The baby was not fine, the heart would not sustain life, the boy would not be born whole. I would not be able to recover from the ongoing surge of bad news I had endured since first discovering the long-awaited good news that I was pregnant, followed almost immediately by the declaration from a gynecologist that things did not appear normal.

Since I was a little girl, I have told stories, happy and sad ones, sometimes aloud when I was alone, but more often than not in my head, playing out all the possibilities of what I had just witnessed or imagined. Later, I would start writing them down, but many more were told to the wind than ever landed on the page. At my dining room table, those paint strokes that brought to life the animals that did eventually make it onto nails in F_____’s room were the audience to a novel’s worth of chapters that I tried to work out to predict what was in store for my husband and me as we held our breaths through week after week of stress tests, ultrasounds, and fetal monitors until the child’s birth was eventually induced because the specialists worried about what all those reports meant over time for the viability of the baby and the life of his mother.

To this day, F_____ does not resemble me physically in any way. He has his father’s blondish-brown hair. He also has a head of glorious curls that are neither too tight nor too loose. Before he was born, in my imagination he was a dark haired, athletic boy with clear blue eyes, a tall thick body, and freckles dotting his arms and legs like constellations in the sky. For real, he is slim with an arrow straight stance and a photographic memory. At 5 feet 6 inches, he has striking green, widely spaced eyes and skin that is pale and pretty, similar to the complexion of his father in his baby, toddler, and adolescent photos. And the glorious curls are more likely a result of the single gene change F_____ eventually was diagnosed as having through genetic tests that occurred about four months after his birth.

We call F_____ “The Imaginator.” By we I mean my husband, F_____’s sister, and me. He got this nickname because he used to walk around his room, the dining room table, around the lake near our house, and just about anywhere else talking out his stories. For years we have said to him, “Don’t do that out loud in front of other people; they will think you are weird, that something is wrong with you when you talk to yourself.” But he really only started listening to us around the age of thirteen. Even now, though, I can see when he is imaginating. He has a smile on his face and his eyes are focused off in the distance on some immovable object, but clearly there is a lot more happening than an observer can guess. If you disturb him now, he will tell you he is busy imaginating and to leave him alone for a couple of minutes. The short films and stories he has created and narrated to date are proof that he has a gift, a talent for this kind of dreaming. He shares the finished products with audiences; only his family knows how the stories begin.

In my long car rides with him, I acknowledge to myself that mother and son have something very important that we share, born of genetics or nurturing, I don’t know. Only F_____ does not worry about what other people will think when he narrates his stories aloud. I have never been caught doing so, even though I realize now that imaginators are not uncommon in this family.

But the thirty-four-year-old who sat and painted while conjuring the story of her child’s birth and the story of the rest of her life, happy and sad versions, did not know and could not author the real endings and beginnings that have written themselves since F_____’s birth. She did not know that there were harrowing days in front of her, that there would be cruel and ignorant physicians and family members who would say all the wrong things and make all kinds of wrong assumptions. That there would be many more triumphant times when F_____’s brilliance and humor would make her forget, sometimes for whole stretches of a day, that he had a gene that remained turned on and could not be turned off. Or that she would find a network of people with children, grandchildren, husbands and wives, siblings and cousins like F_____ who would offer guidance, love, and the reality that “unknowing” is the real state-of-affairs for most of us and that this continues forever, until it does not.

His heart is stable until it isn’t. He is smart and kind and loves music and suffers no pain, until the joints swell or the hearing suddenly progresses from a mild loss to a severe one. The unpredictability is hard to comprehend as much as the confirmed diagnoses: there is indeed a bleeding disorder, so contact sports must cease.

Stroke after stroke, I tried to pile on paint over pencil marks to hide physically the lack of artistic ability and ultimately the recognition that I have no control over much in my life. Word after word, ones read aloud to my husband on pages that I filled with stories and ones that I voiced aloud to no one but myself during long car commutes, could not change anything for real, except that they made me feel better and made me believe that the parable is the vehicle for making sense of feelings and realities that are otherwise impossible to comprehend and still live. Paint over pencil created a room of love for a child. Words on paper created stories that I wanted to tell for no one but me, because I knew at least this much: something had to be done to keep me alive in the face of the ability to imagine the very worst alongside the very best.

I am still writing in my mind and in print the story of F_____ and me and our beginnings together, and I know I will for the rest of my life.

Every weekday morning around 5 a.m. from mid-August until mid-May, I have knocked on my teenage son’s bedroom door, entered the room, turned on his desk lamp, and crooned in a high-pitched, tuneless voice: Dear F_____: I regret to inform you that it is time to get up. “STOP,” he groans, turns his head toward his wall, acting like I have hurt him physically with my voice, but by the time I descend the steps, walk across the kitchen floor and into my own room, the water is running in the upstairs bathroom, and the hum of his voice will reach me when I step into my own shower, hoping to steal the hot water from him first before he steals it from me.

Leave a comment